Life hack

Friday, August 11, 2017

A cup holder. A cellphone mount. A tray just right for a laptop.

To Nicholas Guarino, 20, these are more than handy little devices. They’re keys to a future that includes college, his own place and a career as a writer.

That’s why, in a room at the Illinois Center for Rehabilitation and Education-Roosevelt near campus, two Assistive Technology Unit (ATU) staff members hunker down by Guarino’s wheelchair. Guarino has limited use of his right hand, so it’s important to have everything he needs in a convenient place. Jim Graham, ATU equipment specialist, and Kathy Hooyenga, ATU occupational therapist, adjust the angle of the cup holder and fiddle with the placement of the phone mount.

Guarino reaches for his water bottle, takes a sip, puts it back. He opens his cellphone case, texts a message, closes the phone. He opens and closes the laptop.

“Woo hoo!” he says with a big smile. “This is cool.”

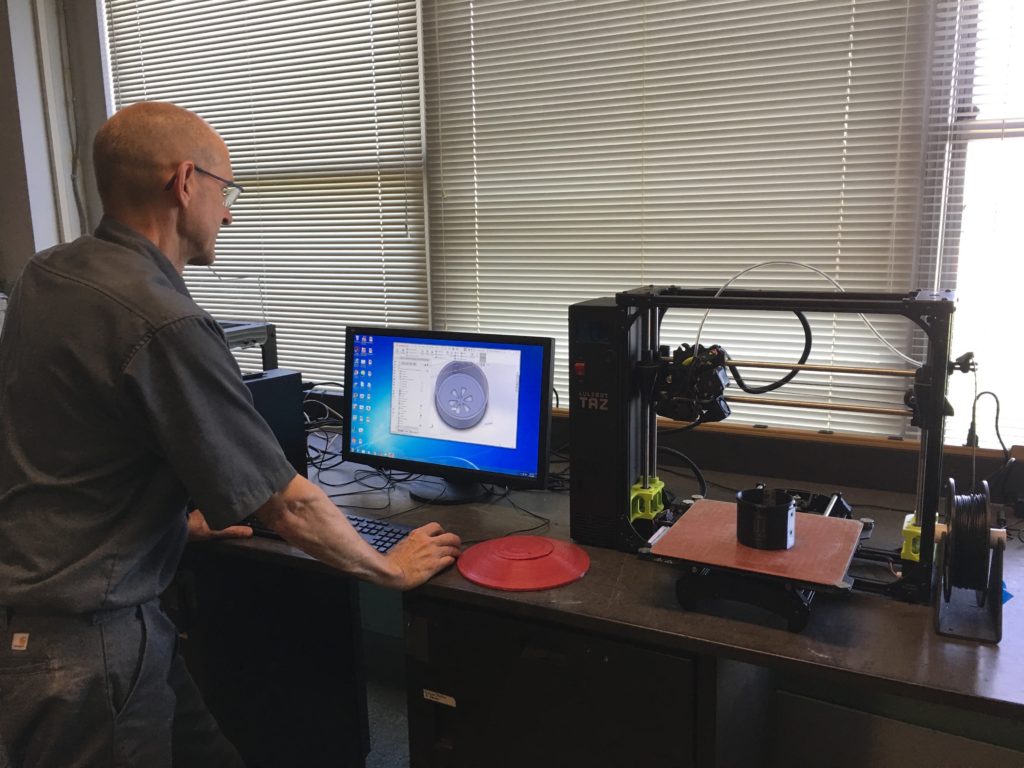

Success! But wait—what about the stick Guarino needs to press elevator buttons? The three of them try different options. Later, in the ATU workshop, Graham will design and create an ingenious but simple solution on a 3-D printer.

“Jim is phenomenal,” Guarino says.

Goal: independent living

For 26 years, the Assistive Technology Unit in the Department of Disability and Human Development has helped thousands of people with disability maximize their independence. The ATU also increases awareness of assistive technology by educating teachers, therapists, UIC students and others.

“Disability issues are social issues, manifested in the built environment,” says Glenn Hedman, ATU director and clinical associate professor of disability and human development.

The ATU’s staff consists of 20 full- and part-time staff including engineers, architects (including three graduate students), occupational therapists, physical therapists and speech-language pathologists. They adapt, adjust or create devices and tools—from cup holders or software apps to contractor-ready drawings for making a home accessible. Several ATU devices have been licensed for commercial production.

“That’s what’s so strong about our clinic. We have the ability to customize what the individual needs,” says Hooyenga, clinical assistant professor of disability and human development, who has a master’s degree in rehabilitation technology.

The ATU is the largest mobile assistive technology clinic in the nation, serving clients in 13 counties in Northeast Illinois. With nine mobile vans, “we can go where the client is,” says Hedman, who has a bachelor’s in bioengineering and a master’s in civil engineering from UIC.

ATU staff travels to homes, schools, work sites and day programs, teaming up in different combinations depending on the case:

- A physical therapist and a rehabilitation engineer modify a client’s wheelchair. The physical therapist determines optimal positioning for the client in the wheelchair, while the engineer works on wheel placement or a specialized power controller.

- For a client on the autism spectrum, a speech-language pathologist works with a rehabilitation engineer to devise a system of visual guides in the home to keep track of schedules and chores.

- An occupational therapist, engineer and equipment specialist create an adaptation for crib safety latches so that mothers in wheelchairs can reach their babies, while keeping the little ones secure.

- An equipment specialist and occupational therapist devise a mouth stick holder for an employee at a suburban park district who enters class registrations into the computer by tapping his keyboard with the mouth stick.

- An occupational therapist, physical therapist, rehabilitation engineer and equipment specialist provide a combination of devices and strategies to help a mailroom clerk achieve the required productivity for his job.

In the ATU workshop in the Disability, Health and Social Policy Building at 1640 W. Roosevelt Road, there are computers, table saws, welding equipment and—most useful of all— several 3D printers.

Before the advent of 3D printing, when a client needed a device like a cup holder or phone mount, “we would try to find something on the market, but it would be ‘close but not quite,’” Graham says. “Now we can create a holder the exact size of the client’s water bottle. If they upgrade to a different phone, with the software we just go in and adjust the dimensions and print a new one.”

The people who work in the ATU like problem-solving. They also like the direct feedback from clients. “It gives me a lot of satisfaction, seeing how assistive technology helps people,” says Sathya Subramanian, an ATU computer specialist who earned a master’s in bioengineering at UIC.

“The work we do can have a real and positive impact on someone’s life,” says Ron Schon, ATU architect and retired associate director of the UIC Office of Capital Programs.

Partnerships

Cup holders and phone mounts are the most frequently requested items when ATU staff make their twice-monthly visits to the nearby Illinois Center for Rehabilitation and Education- Roosevelt, a residential center and school for young people learning the skills to live independently. “Being able to get your own beverage is very important,” Hooyenga says.

Students at the center want easy access to their cellphones, says Becki Heimerle, a speech pathologist at the center. Like most young people, they are obsessed with texting and social media, whether they do their texting using fingers, a mouth stick or eye tracking.

Subramanian sets them up with Google Maps so they can navigate campus when they head to college, and financial apps so they can pay their bills—“tools for independence,” he says.

Several years ago, the ATU and the center obtained a grant from the Illinois Department of Human Services to set up four accessible computer lab-classrooms. The Art Technology Lab is a favorite. Students design posters, T-shirts, flyers—even yearbooks and a cookbook—using assistive technology like eye gaze, head mounts and joysticks to control the software.

“We wanted to develop a truly accessible lab where kids could experience art,” Heimerle says.

The ATU is working with Access Living, a disability advocacy nonprofit, to assist Cook County residents affected by the Colbert Consent Decree. The 2011 court ruling requires the State of Illinois to help adults with disabilities, who qualify under the conditions of the decree, to move out of nursing homes and into independent living.

For example, ATU physical therapists and engineers help Colbert Decree clients with equipment for mobility. Staff architects draw up plans to make the new home accessible, then oversee the remodeling. Occupational therapists provide low-tech assistive technology to assist with meal preparation and other household tasks.

Speech-language pathologist Patricia Politano, clinical associate professor of disability and human development, designed visual aids to help caseworkers communicate with Colbert Decree clients who have impaired speech.

Politano, who has a Ph.D. in disability studies from UIC, also advises Illinois schools on technology for augmented communication. She led two studies for the Coleman Foundation to determine which software apps people with communication impairment prefer, and how they use them.

“There’s been great progress with new technologies that have built-in accessibility features,” Politano says.

The ATU and the UIC School of Public Health recently completed a study for the Federal Emergency Management Agency, in partnership with Ohio State University, that evaluated emergency evacuation devices for people with disabilities.

In another project, Hooyenga is working with Drew Browning, emeritus faculty in art and design and engineering, teaching a class on designing adaptive controllers for games and other online use.

Training

The Assistive Technology Unit offers undergraduate and graduate-level courses and a certificate program in assistive technology.

A new federally funded, five-year program in collaboration with the College of Education will train Illinois elementary, middle and high school teachers as leaders in assistive technology implementation, assessment and policy.

“There aren’t enough experts. We want to get away from the expert model and have more leaders throughout the state,” says Politano, co-principal investigator of Project ATLiS (Assistive Technology in Special Education) with Daniel Maggin, assistant professor of special education. “The more people we can train, the more students can benefit from assistive technology,” she adds.

The project will fund training for more than 50 educators in a 16-month program that includes courses in special education and in disability studies. The first group of nine, selected from 60 applicants, started classes in January. Application deadline for the 2018 session is Oct. 1.

Moving forward

Technology continues to advance, bringing new tools that increase independence for people with disability. Interest in tackling the challenges of disability is growing in the do-it-yourself “maker community” and among students in fields like engineering and architecture.

There’s a problem, though: who pays for this new technology? For example, insurers will cover “dedicated” computer and tablet-based devices that have communication apps with no access to the internet or other functions. But iPads, which cost significantly less, are not considered “durable medical equipment,” so insurers won’t pay for them.

The state’s dire budget situation has also impacted the ATU. Cuts in funding from the Illinois Department of Human Services means some services are no longer covered.

“The technology is out there. The research is out there,” Hedman says. “The question is, how to fit developing technologies into systems such that third-party payers will cover them.”

In the meantime, the ATU continues its mission to overcome challenges, big and small. “What we do makes such a difference for people,” Hooyenga says. “It’s the best part of the job.”