Data-driven

Monday, February 19, 2018

Mary Khetani, assistant professor of occupational therapy, is developing apps for the parents and families of children receiving early intervention services, to give them a more direct role in reporting progress and setting goals for their child’s treatment.

The larger goal is to transform what is now a paper-based, face-to- face, provider-driven process of assessment and evaluation into a system that offers electronic options to gather and use data from providers and families.

“The idea is to improve how we systemize the information we collect from individual families to improve their child’s care, and use that information collectively to build knowledge around the trajectories and participation outcomes of children across a variety of conditions and diagnoses—how they experience rehabilitation, and how their experience of rehabilitation relates to outcomes that matter to families over time,” said Khetani, director of the Children’s Participation in Environment Research Laboratory (CPERL) in the Department of Occupational Therapy.

Early intervention offers therapies and support services to children age three and under who have developmental delays or disabilities, and their families.

“We know from the literature and from clinical experience that having families as part of the early intervention process, at every step, influences the child’s outcome in learning and community participation,” said Ashley Stoffel, clinical associate professor of occupational therapy, who collaborates with Khetani on research related to family engagement in early intervention.

Accessibility laws require that parents and families must be equal partners in the multidisciplinary care team, Stoffel explained.

But that’s not as easy as it sounds; Khetani knows this firsthand. She began her career as a pediatric occupational therapist at an early intervention program, where she interviewed parents, then wrote pages and pages of notes. But the information gathered by this time-consuming process was not systematically integrated into decisions about care, or used to look for trends in goals and outcomes for families served by the program.

“The assessment tools we primarily relied on were designed for professionals, who are with the child for maybe an hour a week,” said Khetani. “But the parent is with the child most. The parent’s voice is so important to the care process, but we didn’t have feasible ways to systematically capture that perspective to plan and monitor care.”

Her “clinical irritation with the way functional outcomes were being documented” propelled Khetani to a Sc.D. in rehabilitation sciences at Boston University, a postdoctoral fellowship at Slone Epidemiology Center, an academic career at Colorado State University and finally to UIC.

With continuous funding since 2012 from the National Institutes of Health and organizations such as the American Occupational Therapy Foundation, CPERL is partnering with parents and providers to develop apps that parents can use to record their child’s participation in activities at home and in the community. In her research, she works with collaborators in various disciplines at institutions including the Colorado School of Public Health, McGill University, McMaster University, University of Texas Medical Branch and Jonkoping University in Sweden.

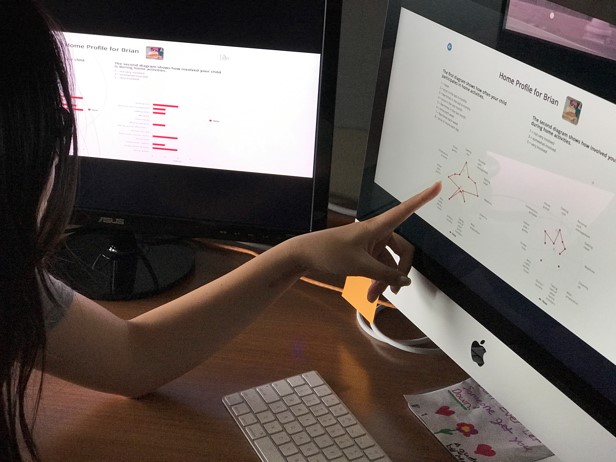

Khetani has been working with colleagues to develop and use an app called the Participation and Environment Measure (PEM).

“We’re developing tools that allow the family to be an equal partner in setting the goals and priorities of care.”

The first part of the app, an online questionnaire with an automated and parent-friendly report feature, was tested in 2013 with about 400 families. The research team is moving into the second phase, evaluating how the online questionnaire could be used, with early intervention and early childhood agencies in Denver and Chicago. CPERL also worked with parents and providers to add a new feature to the app that provides care planning support for parents.

“The feedback from parents has been positive,” Khetani said.

“It helped me clarify and specify some of my priorities with regard to the things I’d like to work on with my kid,” one parent responded in a survey about the app.

“It broke down all the parts to my child’s day,” another parent reported. “It helped me think about each part of the day and every activity he’s involved in. It is helpful when thinking about if there are any areas that need improvement.”

Partnering with providers in this next phase is important to the research, Khetani said.

“We’re learning so much about real-world implementation, about how to partner with providers to figure out how the questionnaire works in practice, how it could integrate into provider workflow, and how to build research capacity in practice,” she said.

Her research team talks with providers about the ways PEM can enhance care. “We would never assume that technology can replace the therapeutic value of face-to-face encounters,” Khetani added. “But technology can be used to customize care so that all encounters, face-to-face or online, are high quality.”

Alexa Greif ’13 MS OT, an occupational therapist and director of feeding therapy at Blue Bird Day Therapeutic Preschool and Kindergarten in Chicago, is working with Khetani in testing the new part of the PEM app.

Greif, who works with children who have autism and sensory processing disorders, said the app could help demonstrate the effectiveness of care to both families and insurers.

“This is an opportunity to communicate that the kind of therapy we’re providing does make a difference,” said Grief, who expects to complete her doctorate in May. Khetani said her experience as a practicing occupational therapist influences her research.

“It’s particularly rewarding because I began my career in early intervention,” she said. “To do research and bring it back to the same service context in which you began your career—it’s full circle.”